The Tourism Life Cycle: Part One

I grew up in the small town of Truckee, California. As a child, I was oblivious to big-picture concepts like economic development and the impact of the tourism industry. I remember frequenting local resorts and paying five dollars for local student ski passes on Sundays. I have fond memories enjoying our region’s most spectacular terrain from the seat of a chairlift.

My Hometown Experience

Through my collegiate studies, I began to notice my hometown’s reliance on tourism. As I returned home to work in the industry during summer and winter breaks, I continued to recognize how important the industry would be as a regional economic driver for years to come. I also observed, somewhat unfortunately, how the increased emphasis on serving the needs of temporary visitors was affecting resident’s attitudes towards tourism.

Sadly, many of the ‘local’ benefits from tourism have been slowly stripped away as the industry has shifted their focus to meeting the needs of part-time visitors and second-home owners. While the economic benefits of catering to these market segments are clear, the needs of the people responsible for delivering a first-rate tourism experience cannot be ignored.

Many full-time Tahoe residents work in the tourism industry and are regularly responsible for interacting with guests. Despite working long hours, many locals are struggling to stay afloat as the region’s cost of living continues to rise. While planners must be compensated for ensuring adequate accommodations for massive influxes of visitors, our region’s largest tourism corporations have the ability to more adequately provide for the needs of the employees that make daily impacts on visitor experiences.

Moments of Truth

In tourism studies, there is a concept known as ‘moments of truth’. Visitors have multiple moments throughout their stay. One example is the visitor’s initial encounter with resort staff upon arriving at the destination. This initial encounter can make or break the visitor’s experience, and many moments throughout their stay will impact whether or not they’ll return to that destination in the future.

In the tourism industry, employees at all organizational levels affect the guest experience. If resorts wish to deliver a top-notch tourism experience, employees at all levels must have their needs met so that they are excited to show and meet visitor’s needs every day. Happy hosts lead to satisfied visitors, and satisfied visitors are more likely to become repeat visitors.

Tourism Through a Local Lens

North Tahoe’s dependence on tourism has grown rapidly during the past decade. In Truckee, this has led to infrastructure improvements and a boom of tourism offerings. Many locals, however, have grown concerned about the dangers of relying too heavily on tourism as an economic driver, especially if economic gains aren’t being used to improve local quality of life.

According to City-Data.com, per capita income in Truckee was nearly $36,000 in 2013. This is up from about $27,000 in 2000, and although average income has risen, so have median values for houses and condos. The average home in Truckee went for almost $419,000 in 2013, which is an increase from just over $240,000 in 2000.

Median income has increased by nearly 40 percent, but property values have also risen by nearly 75 percent. Median gross rent in 2013 was over $1,400 per month, which equates to about half of the average annual per capita income. Despite the high cost of living these numbers suggest, Truckee’s cost of living index, as of March 2013, was 99.9, just below the U.S average of 100.

Averages, however, don’t tell the full story. When it comes to distributing the economic benefits from tourism, there appears to be a discrepancy between median income for all residents of Truckee and the reported average base salaries of the region’s highest-paid public officials and private CEOS.

Published last November in the Tahoe Daily Tribune, this article examined the base salaries of top leaders in 21 of the region’s public agencies. According to the analysis, the average base salary for these leaders was three and a half times higher than the average American worker. The comparisons made in the article include information on base salaries only, and while top public officials make 3.7 times more than the average town employee, this pales in contrast to the private industry, where CEOs often make in excess 300 times more than the average private employee.

These officials are undoubtedly adequately compensated for the jobs they do in overseeing massive annual budgets and managing large teams of employees. Tourism, however, has the potential to improve the quality of life for full-time residents working at every level of every industry. Fortunately, another Tribune article published back in April details greater efforts to gather input from community members in the formulation of a master tourism plan aimed at improving the tourism experience in the region over the next ten years.

Local to Global

This is a very promising sign. Full-time residents must demand a say in the distribution of economic gains from tourism, as well the best ways to spend public funds to improve future tourism offerings. They should also express their opinions on how tourism profits will be used to improve the quality of life in the region. This issue hits home, for me, in Tahoe, but local input should be applied to existing, and up-and-coming, tourism destinations throughout the world.

Many developing nations today are utilizing tourism to bolster economic viability. However, when locals don’t possess the educational background necessary for them to play an integral role in the tourism planning, development, and delivery processes, their needs are easily subjugated to those of the investors and stockholders funding the multinational corporations that are responsible for global tourism planning and development.

Healthy economic gains and vast improvements in quality of life are promised often, but the delivery of real, tangible benefits still appears to be lacking on a global scale. In part two of this brief blog series, we will examine the evolution of the tourism life cycle, including a look at the progression of host-visitor attitudes during the course of this cycle.

The Tourism Life Cycle: Part Two

In any tourism destination, the local population must possess the capacity to maximize the benefits of increased visitation. Investments in sustainable development must be accompanied by investments in local education, especially in nations where funding for education is limited. Without such investments, it will remain difficult to achieve positive and sustainable, regional economic development, as well as improve quality of life for locals.

In many cases, a significant percentage of the direct profits from increased tourism visitation escape the local economy. Often, this means that local benefits only extend so far. When locals begin to realize the extent of their “glass ceiling,” many begin to regret their willingness to open their doors so eagerly. In this case, a dangerous rift may form between visitors and the host population. Refer to the first part of this essay for my personal experience in my hometown.

Butler’s “Tourism Life Cycle”

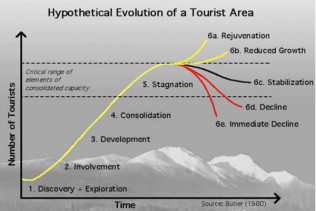

In 1980, Professor Richard Butler outlined six stages in the tourism life cycle. Butler suggested that every tourism destination exhibits an identifiable evolution process. In cases where tourism is overly relied upon as a primary economic driver, local economies become devastated when the destination rapidly declines, both in terms of offerings and popularity.

Butler explains his model well:

“Visitors will come to an area in small numbers initially, restricted by lack of access, facilities, and local knowledge. As facilities are provided and awareness grows, visitor numbers will increase. With marketing, information dissemination, and further facility provision, the area’s popularity will grow rapidly. Eventually, however, the rate of increase in visitor numbers will decline as levels of carrying capacity are reached. These may be identified in terms of environmental factors (e.g. land scarcity, water quality, air quality), of physical plant (e.g. transportation, accommodation, other services), or of social factors (e.g. crowding, resentment by the local population). As the attractiveness of the area declines relative to other areas, because of overuse and the impacts of visitors, the actual number of visitors may also eventually decline.”

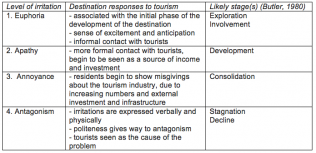

Doxey’s Irridex

Five years before Butler proposed his model, George Doxey examined the evolution of host-visitor interactions. His findings helped him develop what is now known as Doxey’s Irritation Index, or “Irridex,” for short. Doxey’s model suggests that attitudes amongst the host population in a given destination are likely to progress through four distinct “levels of irritation.”

Most host populations begin with excitement and anticipation. Tourism planners and developers promise substantial economic gains. The idea of improving the local economy and bolstering the regional quality of life while welcoming guests from around the world and sharing a slice of local culture appears to be a win-win. In the initial stage of “euphoria,” visitors are welcomed with open arms. Unfortunately, planning to sustainably meet the inevitably variable demands of visitors is often minimal.

Slowly in some cases, and more quickly in others, the host population will begin to take visitors for granted. Interactions between hosts and visitors become more formal and a destination’s reputation for boasting a warm and welcoming local population starts to become compromised. This is known as the stage of “apathy.”

When any given destination reaches the saturation point, host attitudes quickly turn negative. This level of irritation is characterized by ‘annoyance’. Some locals may begin to express concerns and misgivings about inadequacies in their slice of the “tourism pie.” In response, many planners mistakenly attempt to keep a destination viable by increasing infrastructure, rather than limiting growth.

In the fourth and final level of irritation, categorized as “antagonism,” members of the host populations reach their breaking point. In the worst cases, this results in direct host-visitor conflicts, as more hosts start to openly show their frustration. Despite growing tension, planners often increase destination-marketing efforts in an attempt to shore up the destination’s deteriorating reputation, although it may be wiser to limit growth and seek a healthy means of alleviating conflict, such as dispersing benefits more equally.

The Need for More Holistic, People-First Development

Tourism, while touted as an economic savior for many developing nations, can have devastating effects on destinations that are ill-prepared to truly benefit from a boom in year-round visitation. Pollution, widening income gaps, and tense interactions between hosts and visitors are just a few examples of the negative effects of hasty tourism development.

When pursued in an ethically responsible manner, however, opening new destinations to tourism visitation has the potential to break down cultural and ethnic divides, smash class barriers, and improve global quality of life. While many destinations appear prosperous from the friendly grounds of the resort, locals living just miles down the road still face with major challenges, including, but not limited to, lack of access to clean water, healthcare, and education, as well as high rates of infant mortality and below average life expectancy.

As a rapidly expanding global industry, tourism development should be pursued as a tool for improving the quality of life around the globe. A continued adherence to development initiatives that serve corporate interests over the needs of the world’s impoverished and disenfranchised populations will continue to stymie the industry’s ability to reach its full potential.

Changing Gears

Shifting the purpose of tourism’s current “development mission” is no small task, but the corporations driving global tourism development must be held accountable to the pursuit of an ethically-sound vision. We can start by increasing awareness of the all-too-often unequal distribution of tourism “benefits,” as well as investigating how the industry can contribute more positively on an international scale.

Fortunately, there are already many organizations committed to these purposes. If momentum is to continue in a positive direction, however, the individuals that work in, and rely on, the tourism industry for their livelihood must have an equal seat at the table. Please visit the United Nations Foundation’s siteto read more about efforts to promote sustainable tourism development worldwide!

Hi, this is a very interesting topic. What is it about Disneyland that it makes people so excited to go with their families and spend all their money? Then have it be the most memorable experience of their lives?

Different personalities effect what the person is wanting in their traveling experience. Introverts may prefer a quiet isolated place. Extroverts the opposite.

Hey Jake! I do agree that each individual is looking for something different in their travel experiences. But the idea of the tourism life cycle is that we need to find ways to avoid apathy creeping in. When locals start to feel disenfranchised with tourists, this can lead to conflict, which is a lose-lose situation for tourists and locals alike!

Our local government here in the province of Camarines Sur in the Philippines is aiming to boost tourism. They have realized that it can be a main source of revenue given that there are many potential tourist destinations here such as beaches, wake boarding complex, caves and water falls. With our explanation here, I got the impression that you are also good at giving lectures to government units as far as boosting tourism is concern. Can we invite you for a talk on tourism sponsored by the local government?

Hi Gomer! I am humbled by your interest and would like to discuss this further. Please shoot me a direct email!

Thanks for your comprehensive article about tourism. I love travelling very much and try not to impact the environment in a negative way but it’s not only about me, obviously. You are right that when a destination reaches a saturation point, the experience and attitude turns negative.

For me, a perfect example of how the tourism is used to the benefit of the local people while preserving the original beauty of the place is Nerja in southern Spain. It is very rare; it is so common that there are high-rise buildings just next to the beautiful traditional house that completely damage the view / landscape.

Do you work in an organisation supporting sustainable tourism development? It is definitely necessary to work on that.

Hi Lenka! I appreciate you bringing up a place that you feel is a good example of the balance that a healthy tourism economy requires. I don’t work in an organization supporting sustainable tourism development. But as of next summer, I will be guiding my own backpacking trips in the Sierra Nevada mountains and leaving the places we travel better than we found them will be a big part of my trips!

I’m not that educated on the finer aspects of tourism or the economy thereof but it seems that from my perspective, in my limited travel experience, It’s the “How much can we get them to spend?” attitude instead of “How or what can we do to give them, the tourists, the best experience while they are our guests?”.

Don’t get me wrong. I understand the value of the dollar, pound, peso or ? to the person running the business. They depend on the tourist to make ends meet. I like the idea of collecting a memento from a vacation to a place I’ve never been but for me, it’s more about “seeing” than “spending”.

The people trying to make a living, the regular employee, don’t seem to have a fighting chance either according to the statistics you relate here. I see the same thing happening in my own country/province. High rents and low wages. It’s not right.

Wages are not keeping up with the cost of living and as you well said, it seems the only ones that really benefit from tourism are the CEO or the owners of the operation. The employees get left behind and have to work more than one job just to make ends meet.

Tourism is, for sure a benefit to the local business economy but those involved, those who own those tourist businesses need to take care of the people who are working for them.

Maybe I’ve missed the mark of your post but it tells me that there are some things that can be done better with less frustration on the other end?

Wayne

I think you bring up a great point Wayne, in that the focus is on dollars spent rather than experience(s) offered. And yes, the goal of the post is to relate that things could be done better/healthier for all those involved. I grew up in a ski town that also relies heavily on tourism throughout the summer season. All too often, it doesn’t seem like the larger organizations aren’t adequately compensating employees. Most folks I know here are working two (sometimes three) jobs to make ends meet, even during the busiest tourist seasons. What country/province are you based in?!